For time is the longest distance between two places.

Tennessee WilliamsWe, as humans, have contemplated, deliberated and sought to understand the concept of time, since, well… the beginning of time. The inevitability of its passing and the ensuing impact of its very existence on human lives has been a source of constant wonder in our ever-increasingly hectic lives. Each and every moment seems to be dictated (directly or indirectly) by the omnipresent ticking away of seconds, minutes, and hours.

The Persistence of Memory, Salvador Dali

While we spend our days tethered to the scientific and factual aspects of time, we have yet to master the less tangible perception of time. In particular, I often wonder about things such as how can an undisputed span of 60 seconds at times feel like an eternity and others, a mere fraction of a heartbeat … or how can one second change your entire life… and how is it possible that a single day can weigh so heavily on one person, while just barely touching another?

Within the certainty of time as we know it, our very human interpretation of each moment, often quite simply defies logic.

This is especially true in the hospital, where time becomes the primary marker by which you measure most anything of importance. Medication dispensing, mealtimes, bathing, therapy appointments, vital sign assessments – they all take place within a structured schedule. The freedom to make these, or other seemingly minor, choices is forfeited upon hospital admission. Occasionally, you may have some small say in bits and pieces of your day, but most often, it’s just another area of your life that you no longer control. Eventually, you become somewhat accustomed to having decisions made for you and, at times, even revel in the simplicity of the mundane monotony. It can actually be comforting during a time period of so many unknowns…until, of course, it isn’t. Until you wait on edge for hours for the right doctor to show up and give you the days latest test results, or the lab is backed up, or you have been wheeled to a scheduled procedure only to spend an awkward half hour in the cavernous hallway making forced conversation with your transport. In these moments, where there seems to be an excess of time to kill, the clock ceases to provide comfort and rather, becomes a mocking face with hands pointing obnoxiously to each moment that the world  goes on without you.

goes on without you.

When the days begin to blend together in your mind and the steady rhythm of the ticking clock means less with every moment, standard labels of time aren’t enough to significantly differentiate one instant from another. You begin to track the passage of time in other ways – through visiting friends and family, menu variations and nursing shifts. The length of your stay is no longer measured by weeks or even months, but instead, by how many treatments you’ve had and how many you have left. The days of the week cease to exist, replaced by what are known as simply “good days” or “bad days.”

Time is all you have and yet, it somehow ceases to exist.

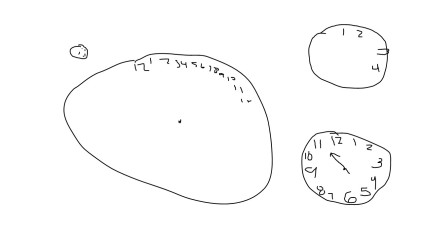

In the world of brain injury diagnosis and recovery, progress is further tracked and documented through numbers and time in lieu of laboratory data. Your prognosis is evaluated based on the number of times you’ve physically attacked someone, how long you had to be in restraints, and how many personality changes or emotional breakdowns you’ve had that day. Deeper cognitive abilities are measured by how many words you can recall from a verbal list 5, and then, 15 minutes ago; your ability to count backwards in increments of seven; and, yes, even by your ability to draw a basic clock correctly. Known simply as The Clock Test, this activity is used to assess neurological abilities that are otherwise, generally immeasurable. The patient’s mental capacity is scored based on their ability to draw an enclosed circle, add appropriately spaced numbers and indicate a specified time.

Clock test rendering

Throughout my own hospital and rehab tenure, I was given this particular test many times with results ranging from minuscule drawings of incomprehensible images, to a “clock” with numbers 1-12 all squished in the upper right quadrant, to, finally, a correctly drawn timepiece, my success only slightly diminished by the inability to identify a specific time.

Other immeasurable areas of progress were tracked on a small whiteboard that hung in my hospital room. Each day the nurses would update the day, date and names of staff assigned to me for that shift. Often treatments and procedures were also tallied on that board. And this, too, became a ‘test of time,’ as often the staff would begin my assessments by asking me if I knew the day or the date, until eventually, although still lacking full cognitive abilities, I began to catch on to the fact that I could simply read the correct answers from the board on the wall. And on one particularly bad night, in a fit of rage and frustration I yanked the board down and violently wiped it clean in a defiant demonstration of anger. Looking back, I can see that incident for what it really was: a pitiful attempt to “erase” my time in the hospital, to push the delete key on this part of my story, to wipe the very literal slate clean…If only it were that easy!

Recovery, acceptance, healing…these things DO TAKE TIME. Or so we are told. Although, that sentiment offers little comfort in our day-to-day lives – specifically, as I wait in doctor’s office waiting rooms reading year old magazines until my name is called; or as I stutter through completing a verbal thought, while silently struggling to recall the very simple name of a very common object; or as I spend several minutes repeatedly re-reading a single paragraph only to realize I cannot recall what it was about. But, then, true to its contradictory nature, time also has a way of sneaking up on me in good ways—where its passing goes by, pleasantly unnoticed — during a full day of hard work, or alternatively, a day off with no specific agenda; upon waking from an uninterrupted nap or finding myself immersed in a good book or movie. On these occasions, I momentarily break free of the constraints of time, and just BE, and that is enough.

They say that, “time waits for no (wo)man,” so, I say, we might as well accept its uncertainty, even bask in its ambiguity, for THE BEST TIME TO LIVE YOUR LIFE IS NOW.

0 Comments